IV. Innovation

The three Nadars’ passion for photography was inseparable from their belief in progress and their ties to the artistic and scientific goings-on of their time. Their legendary adventure, in which works of art commune with both commercial intuition and technical innovation, unfolds before our eyes.

Electric Light

Portraits by Electric Light

The series of portraits by electric light that Félix Nadar produced from 1859 to 1861 was the result of a period of experimenting with magnesium flashes that preceded the famous shots taken in the catacombs and the sewers.

Serrin regulator, Éclairage à l’électricité : renseignements pratiques, chez J. Baudry (Paris), 1879

2nd edition, by Hippolyte Fontaine, fig. 15, p. 54

© BnF, Science and Technology Department, 8-V-2803

© BnF, Science and Technology Department, 8-V-2803

In April, 1859, he presented his earliest test shots in the salons of the circle of La Presse scientifique the same day that the engineer Victor Serrin (1829-1905) demonstrated his electrical regulator. The invention offered precise control over the toxic, overly-bright light from the first batteries. Sittings were organized in late 1860-early 1861 on the furnished terrace at the Boulevard des Capucines studio. A Serrin regulator, activated by a 50-Bunsen-element battery was used. “As night fell each night, the continuity of that then-uncommon form of lighting attracted crowds on the boulevard. Like moths to a candle, many of the curious, whether friends or strangers, couldn’t keep themselves from climbing the stairs to find out what was going on. Those impromptu visitors from all walks of life, including some well-known or even quite famous people, were always warmly welcomed, thereby furnishing us with a free supply of models who were more than happy to volunteer their time to a new experience. Thus, during those evenings, I was able to photograph, among others, Niépce de Saint-Victor, G. de La Landelle, Gustave Doré, Albéric Second, Henri Delaage, Branicki, the tycoons E. Péreire, Mirès, Halphen, etc., etc., not forgetting my friend and neighbor, Professor Trousseau.” (Nadar, Quand j’étais photographe (When I Was A Photographer), 1900, p. 115-116.)

The experimentation concerned both the shutter speed and the development process for the shots taken by artificial light. The gallery of preserved portraits, including the very surprising “Print of the hand of Mr. D***, banker,” palm up, bears witness to the trial and error that was required, until mastery of the light was achieved thanks to the use of “screens of white, blue and pink frosted glass, which were alternated for test shots, as well as various metallic reflectors, mirrors and white cloths stretched to explore the blacks.” “In this way, “ Nadar wrote, “I reduced the pose time to the daylight average, and in the end was able to obtain pictures equally quickly and of absolutely equivalent quality as those I was taking on a daily basis in my studio.”

The Banker D.'s hand (palmistry study), Félix Nadar, 1861

Snapshot taken with daylight. Print made in one hour by electric light.

© BnF, Prints and Photographs Department, EO-15 (22)-PET FOL

© BnF, Prints and Photographs Department, EO-15 (22)-PET FOL

Nadar dreamt of being freed from his dependence on sunlight, which placed a huge financial constraint on his new establishment. Across the street from the studio, at the corner of the future Opera Square, the gigantic Grand Hôtel was then under construction. So he wrote to Émile Pereire, the main investor in both the hotel and Nadar’s own business, to suggest a partnership: the House of Nadar would have the exclusive right to offer guests at the Grand Hôtel the possibility of having their portrait taken, which they could take with them, or receive before leaving the hotel. Nothing ever came of the proposal. It was the second time, after an 1858 patent for aerostatic photography, that Nadar had tried to get photography out of the studio and into the life of the world.

Underground and Underwater

Félix Nadar began experimenting with photography by artificial light in 1859; he applied for a patent for it in 1861. Some one hundred photographs, first of the catacombs, in 1862, then of the sewers, in 1865, constitute the most spectacular application of his technique. These photographic essays actually concerned current events: the sanitizing of Paris imposed by the imperial authorities after the terrible cholera epidemics.

Bones dug up from old cemeteries were transferred to inactive quarries that had been arranged to receive them: these became the famous “catacombs.” Open to the public four times a year, they became a trendy destination for sight-seers. The idea of taking photographs in that sought-after, esoteric place comes from Ernest Lamé-Fleury (1823-1903), Mining Engineer and Quarry Inspector, who appealed to Nadar in 1861: “Using the title The Catacombs, an amateur recently published a short study, of which I naturally procured a copy, in order to learn what was being said abut my dark domain. An awful lithography offers a terribly inexact impression of the ossuary. I would be very pleased, dear sir, if you could let yourself be tempted by the idea of applying your magnificent electric photography to providing a precise and picturesque (judging from the constantly growing number of visitors) representation of one of Paris’s most unusual curiosities […]. »

Lamé-Fleury granted Nadar exclusive reporting rights, put his staff at the photographer’s service and provided him with a kilometer (3,280 feet) of coated wire from by Mr. Baron, a telegraphic-wire inspector in Paris. In return, Nadar would be responsible for all other expenses, and would supply Lamé-Fleury with several copies of the finished photo album. Their correspondence enables us to establish that the report was carried out between February and April, 1862.

Bones dug up from old cemeteries were transferred to inactive quarries that had been arranged to receive them: these became the famous “catacombs.” Open to the public four times a year, they became a trendy destination for sight-seers. The idea of taking photographs in that sought-after, esoteric place comes from Ernest Lamé-Fleury (1823-1903), Mining Engineer and Quarry Inspector, who appealed to Nadar in 1861: “Using the title The Catacombs, an amateur recently published a short study, of which I naturally procured a copy, in order to learn what was being said abut my dark domain. An awful lithography offers a terribly inexact impression of the ossuary. I would be very pleased, dear sir, if you could let yourself be tempted by the idea of applying your magnificent electric photography to providing a precise and picturesque (judging from the constantly growing number of visitors) representation of one of Paris’s most unusual curiosities […]. »

Lamé-Fleury granted Nadar exclusive reporting rights, put his staff at the photographer’s service and provided him with a kilometer (3,280 feet) of coated wire from by Mr. Baron, a telegraphic-wire inspector in Paris. In return, Nadar would be responsible for all other expenses, and would supply Lamé-Fleury with several copies of the finished photo album. Their correspondence enables us to establish that the report was carried out between February and April, 1862.

As for the sewers, their renovation had begun in 1855, under the aegis of Eugène Belgrand (1810-1878), chief engineer in charge of water services and sewers for the City of Paris, which supported Félix’s project. The setup was the same as it had been for the catacombs: same material, same use of models to enliven the scenes and provide scale. As the pitfalls were more numerous, only 23 shots were preserved. While the Romantic reference for the sewers of Paris will always be the famous episode from Les Misérables (1862) in which Jean Valjean escapes through them to save Marius, the Piranesian bowels described by Victor Hugo were already a thing of the past; the system had been radically renovated. The point was not to give the public, which was not allowed to visit them, a shiver of horror or disgust, but to encourage viewers to admire the sanitization work that had been accomplished. That was the only time that Nadar ever paid tribute, albeit indirectly, to the endeavors of the despised Napoleon III.

Nadar’s account of his adventures underground were his contribution to the multiple-authored Paris Guide published in 1867 for the World’s Fair. He then divided them into episodes for his son Paul’s journal, Paris-Photographe, in 1893, and served them up again in When I Was A Photographer, his 1900 memoir. Both series were displayed as outstanding achievements of the glorious House of Nadar, in their studios and at Nadar stands at all the World Fairs until 1900.

In 1899-1900, while he was living in Marseille, Nadar fleeting returned to the subject when, at the request of the Petit Marseillais, he documented enlargement work on the city’s port by taking photographs of construction workers in a pneumatic caisson 30 feet underwater, building the Pinède basin. Nadar’s successors, Detaille and Boissonnas, carried on the reportage until 1904.

Nadar’s account of his adventures underground were his contribution to the multiple-authored Paris Guide published in 1867 for the World’s Fair. He then divided them into episodes for his son Paul’s journal, Paris-Photographe, in 1893, and served them up again in When I Was A Photographer, his 1900 memoir. Both series were displayed as outstanding achievements of the glorious House of Nadar, in their studios and at Nadar stands at all the World Fairs until 1900.

In 1899-1900, while he was living in Marseille, Nadar fleeting returned to the subject when, at the request of the Petit Marseillais, he documented enlargement work on the city’s port by taking photographs of construction workers in a pneumatic caisson 30 feet underwater, building the Pinède basin. Nadar’s successors, Detaille and Boissonnas, carried on the reportage until 1904.

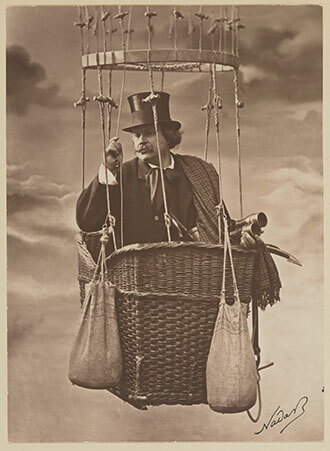

Aerial Photography

Throughout his life, Félix Nadar was wildly enthusiastic about conquering the air. Aside from photography, it was the only endeavor that involved his whole family. Ernestine risked her life through personal involvement in the adventure. In gratitude for his participation in the aerostatic experiments, Félix described Adrien as an “excellent brother.” Paul won fame for his aerial photography, and his contributions to the portrait gallery reveal his close ties with aeronautic circles.

Self-portrait with Ernestine in a balloon basket taken in the studio on the Boulevard des Capucines, Félix Nadar, around 1862

© BnF, Prints and Photographs Department, EO-15 (3)-FOL

Félix was something of a pioneer in the history of aviation for his defense of the theory that, “to win out over the air, one must specifically be heavier than air.” (Félix Nadar, Les Mémoires du Géant (Memoirs of Le Géant), 1865 - Le Droit au vol (The Right to Flight), with a preface by George Sand, Paris, Hetzel, 1865).

In 1863, after meeting Ponton d’Amécourt, a scientist who studied flying whirly toys, Nadar founded the “Society for the Encouragement of Aerial Locomotion via Heavier than Air Craft.” Although he was promoting an understanding of the limitations of ballooning, he still had a huge, 148-foot-tall balloon, Le Géant, built by the Godard brothers at his own expense. Revenue from ticket sales provided the starting capital for the Society. On October 4, the first excursion, taking off from the Champ de Mars, where the Eiffel Tower would be built a few decades later, attracted 200,000 spectators. The accident near Nieubourg during their second flight, which Félix and Ernestine were on, was reported in both the French and international press. Adrien signed the “official” image, based on his brother’s accounts, which was reproduced everywhere.

Although Jules Verne’s character Michel Ardan in From the Earth to the Moon (1865) is an homage to him, after five flights, Nadar was facing 200,000 francs in debt, and he sold the balloon in 1867. Nevertheless, he continued to defend his pet cause. In 1873, the huge goose-feather bird tested by Ader was displayed in the studio on the Rue d’Anjou. In 1909, when Louis Blériot succeeded in crossing the English Channel, it was an opportunity for Nadar to recall his role as a precursor in a congratulatory telegram to the aviator: “In grateful recognition for the joy with which your triumph has filled this antediluvian of “heavier-than-air” before his eighty-nine years are laid below ground.”

Félix put his photographic expertise to the service of aerial navigation. In 1858, he applied for a patent for using photography to plot topographic maps and in strategic military operations. He described his first such success, over the town of Petit-Bicêtre in autumn, 1858, in Memoirs of Le Géant but the print has unfortunately been lost. The image that he presents as the first aerostatic photograph is actually a partial surveyor’s view of Paris, taken from Giffard’s tethered balloon 10 years later. Despite all his efforts, the idea didn’t catch on. In the end, it was his son who could boast of having enabled “aerostatic photography to be adopted by the War Ministry for military services in France” (Paul Nadar, “Progrès et applications de la photographie” (Photography’s Progress and Applications), Paris Photographe, August 1892, p. 325 ). On July 2, 1886, he took about 30 shots between Versailles and Camp Conlie (in the Sarthe) during a six-hour-long flight in the Tissandier brothers’ balloon Commandant Rivière, which achieved a maximum altitude of almost 5,580 feet.

In 1863, after meeting Ponton d’Amécourt, a scientist who studied flying whirly toys, Nadar founded the “Society for the Encouragement of Aerial Locomotion via Heavier than Air Craft.” Although he was promoting an understanding of the limitations of ballooning, he still had a huge, 148-foot-tall balloon, Le Géant, built by the Godard brothers at his own expense. Revenue from ticket sales provided the starting capital for the Society. On October 4, the first excursion, taking off from the Champ de Mars, where the Eiffel Tower would be built a few decades later, attracted 200,000 spectators. The accident near Nieubourg during their second flight, which Félix and Ernestine were on, was reported in both the French and international press. Adrien signed the “official” image, based on his brother’s accounts, which was reproduced everywhere.

Although Jules Verne’s character Michel Ardan in From the Earth to the Moon (1865) is an homage to him, after five flights, Nadar was facing 200,000 francs in debt, and he sold the balloon in 1867. Nevertheless, he continued to defend his pet cause. In 1873, the huge goose-feather bird tested by Ader was displayed in the studio on the Rue d’Anjou. In 1909, when Louis Blériot succeeded in crossing the English Channel, it was an opportunity for Nadar to recall his role as a precursor in a congratulatory telegram to the aviator: “In grateful recognition for the joy with which your triumph has filled this antediluvian of “heavier-than-air” before his eighty-nine years are laid below ground.”

Félix put his photographic expertise to the service of aerial navigation. In 1858, he applied for a patent for using photography to plot topographic maps and in strategic military operations. He described his first such success, over the town of Petit-Bicêtre in autumn, 1858, in Memoirs of Le Géant but the print has unfortunately been lost. The image that he presents as the first aerostatic photograph is actually a partial surveyor’s view of Paris, taken from Giffard’s tethered balloon 10 years later. Despite all his efforts, the idea didn’t catch on. In the end, it was his son who could boast of having enabled “aerostatic photography to be adopted by the War Ministry for military services in France” (Paul Nadar, “Progrès et applications de la photographie” (Photography’s Progress and Applications), Paris Photographe, August 1892, p. 325 ). On July 2, 1886, he took about 30 shots between Versailles and Camp Conlie (in the Sarthe) during a six-hour-long flight in the Tissandier brothers’ balloon Commandant Rivière, which achieved a maximum altitude of almost 5,580 feet.

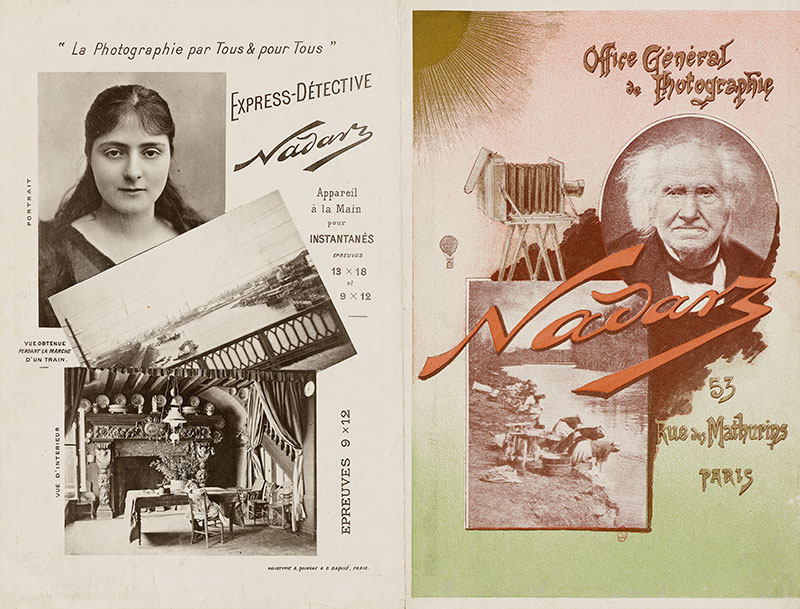

Instant Photography

Reducing how long subjects had to pose was a key issue in photography’s early history. The increased sensitivity of the gelatin-silver process would enable photographers to record subjects in a more lifelike, less posed manner, which in turn allowed the medium to incarnate the very image of modernism. The Nadar studio helped pioneer the development of instant photography commercially. Félix Nadar was exploring the issue as early as 1860. His friendly relations with Désiré Van Monckhoven, who founded a factory producing dry silver- gelatin plates in 1878, meant that both he and Paul became familiar with the process early on. They were in fact some of the very first professionals to adopt it.

Publicité pour l’Express-Détective Nadar, vers 1888

© BnF, département des Estampes et de la Photographie

Paul was an ardent promoter of instant photography. Not only was he France’s exclusive distributor for the American company Eastman, when it began selling the first flexible film and the Kodak camera, he also personally contributed to its development, with the Nadar Express Détective camera in 1888, and Nadar extra-fast plates in 1893. He very much enjoyed the practice, as his numerous private portraits evoking a privileged existence bear witness. The Kodak camera also revived his father’s interest in photography.

Paul Nadar used the new, flexible Eastman film for his photographs of the performing arts and his first photo-report, about the Opéra Comique fire, in May, 1887. He then sold his shots of both the aftermath and the commemorative ceremony to Le Figaro. In 1896, he covered the Romanovs arrival in Paris with his Express Détective.

Paul Nadar’s journey through Turkestan, in 1890, really allowed him to demonstrate the advantages and qualities of instant cameras. The some 1,500 pictures he took with the Kodak and the Express Détective offer images of scenes caught live during the long voyage on the trans-Caspian train line and events he witnessed during the journey. They provide a spontaneous, eyewitness account of the experience. He also promoted a more esthetic point of view, by presenting a scene with a dervish in Samarkand as an “example of the possibility of doing artistic work even with instant photography,” (Paris-Photographe, February, 1892, p. 87).

The First Illustrated Interview

In 1886, Félix and Paul’s steno-photography experiments represented a new step towards achieving immediacy. On the occasion of the centenary of the chemist Eugène Chevreul, Paul Nadar devised a plan to record his father’s interview with the scientist through the mediums of both stenography and photography. Adler’s “phonophone,” which they had originally hoped to use for an audio recording, wound up not being entirely functional in time.

Over the course of three sittings, both at home and in the studio, he took some one hundred shots – with a shutter speed of 1/133rd of a second – of Chevreul in conversation with Félix Nadar, as well as with his son, his laboratory director, and the Chinese ambassador. The interview, which was originally done for L’Illustration, wound up appearing in the September 5 edition of the Journal illustré, entitled L’Art de vivre cent ans. Trois entretiens avec M. Chevreul à la veille de sa cent et unième année (The Art of Living to Be 100: Three Interviews with Mr. Chevreul on the Eve of His 101st Year of Life). It would be the world’s first photographically illustrated interview published in the press (the captions written by Félix Nadar were, however, somewhat more whimsical than the original conversation).

The series was one of the main attractions at the 1889 World’s Fair, and Le Figaro commissioned Paul Nadar to renew the experience for the journalist Charles Chincholle’s interview with General Boulanger later that same year.

The Chevreul interview is seen as a turning point in the development of the illustrated press. In his Nouvelle histoire de la photographie (New History of Photography), Michel Frizot points out that it was the “first attempt at absolute truth and transparency, at the cutting edge of live reporting.” “The novelty consisted in ‘not posing’ [Chevreul is wearing slippers!], and in ignoring the camera; the unique bond between image and speech – which often underpins photography – has been elevated to a principle of knowledge here.”

Over the course of three sittings, both at home and in the studio, he took some one hundred shots – with a shutter speed of 1/133rd of a second – of Chevreul in conversation with Félix Nadar, as well as with his son, his laboratory director, and the Chinese ambassador. The interview, which was originally done for L’Illustration, wound up appearing in the September 5 edition of the Journal illustré, entitled L’Art de vivre cent ans. Trois entretiens avec M. Chevreul à la veille de sa cent et unième année (The Art of Living to Be 100: Three Interviews with Mr. Chevreul on the Eve of His 101st Year of Life). It would be the world’s first photographically illustrated interview published in the press (the captions written by Félix Nadar were, however, somewhat more whimsical than the original conversation).

The series was one of the main attractions at the 1889 World’s Fair, and Le Figaro commissioned Paul Nadar to renew the experience for the journalist Charles Chincholle’s interview with General Boulanger later that same year.

The Chevreul interview is seen as a turning point in the development of the illustrated press. In his Nouvelle histoire de la photographie (New History of Photography), Michel Frizot points out that it was the “first attempt at absolute truth and transparency, at the cutting edge of live reporting.” “The novelty consisted in ‘not posing’ [Chevreul is wearing slippers!], and in ignoring the camera; the unique bond between image and speech – which often underpins photography – has been elevated to a principle of knowledge here.”

Uncropped enlargement of the interview with Chevreul, Félix et Paul Nadar, 1886

© Paris, French Photography Society Collection

The appeal and likely future of the exercise did not escape the attention of the journalist Thomas Grimm, who announced the up-coming publication of the interview in the columns of the August 31, 1886 edition of the Petit Journal in the following terms:

“Every photographer applied for the honor of taking Mr. Chevreul’s portrait. Nadar did more and better. His son, Mr. Paul Nadar, applied the processes of instant photography to speech, thanks to his Eastman films, which take a photographic image in two-thousandths of a second.

This system is sure to be of great service to contemporary journalism, which depends on conversations with prominent men – conversations which go by the barbarian name “interview.”

However attentive and intelligent the writer whose task it is to question a scientist, artist, traveler, elected official, or magistrate is, he might nevertheless report what he heard incorrectly, either because he partially misunderstood it in the first place, or because he didn’t remember it properly.

With the Nadar system, interpretation and guesswork have been eliminated: we get an exact reproduction of every occurrence, every interruption in speech, and every pause that conversation allows. We are provided with a document of absolute historical exactitude.

This is what happpened with Mr. Chevreul, with the exceptionally favorable circumstance that, as he was speaking, instant photography was capturing the movements of his physiognomy. This issue of the Journal illustré will be of great interest.

The text and engravings complement each other, and make one appreciate Chevreul; the incredulous scientist who wants to see to believe, and who is an exalted spiritualist. A man who is implacable against villains and the lazy, but good and kind towards those who work hard.

Nadar had three stenographed conversations with him, documented by photographs; he will publish them in an illustrated book, which we will have the occasion to discuss later [author’s note: the book in question was never published]. For the moment, he has granted exclusive publication of both the text and the engravings to the Journal illustré. Having held both in my hands, I can give you an accurate sense of them already.”

“Every photographer applied for the honor of taking Mr. Chevreul’s portrait. Nadar did more and better. His son, Mr. Paul Nadar, applied the processes of instant photography to speech, thanks to his Eastman films, which take a photographic image in two-thousandths of a second.

This system is sure to be of great service to contemporary journalism, which depends on conversations with prominent men – conversations which go by the barbarian name “interview.”

However attentive and intelligent the writer whose task it is to question a scientist, artist, traveler, elected official, or magistrate is, he might nevertheless report what he heard incorrectly, either because he partially misunderstood it in the first place, or because he didn’t remember it properly.

With the Nadar system, interpretation and guesswork have been eliminated: we get an exact reproduction of every occurrence, every interruption in speech, and every pause that conversation allows. We are provided with a document of absolute historical exactitude.

This is what happpened with Mr. Chevreul, with the exceptionally favorable circumstance that, as he was speaking, instant photography was capturing the movements of his physiognomy. This issue of the Journal illustré will be of great interest.

The text and engravings complement each other, and make one appreciate Chevreul; the incredulous scientist who wants to see to believe, and who is an exalted spiritualist. A man who is implacable against villains and the lazy, but good and kind towards those who work hard.

Nadar had three stenographed conversations with him, documented by photographs; he will publish them in an illustrated book, which we will have the occasion to discuss later [author’s note: the book in question was never published]. For the moment, he has granted exclusive publication of both the text and the engravings to the Journal illustré. Having held both in my hands, I can give you an accurate sense of them already.”

The first photographic interview, 5 September 1886, Félix and Paul Nadar

'The Art of Living to Be 100: Three Interviews with Eugène Chevreul' published in issue 36 of Le Journal Illustré, p. 285

© BnF, Philosophy, History and Humanities Department, LC2-3035-FOL

© BnF, Philosophy, History and Humanities Department, LC2-3035-FOL

The first photographic interview, 5 September 1886, Félix and Paul Nadar

'The Art of Living to Be 100: Three Interviews with Eugène Chevreul' published in issue 36 of Le Journal Illustré, p. 285

© BnF, Philosophy, History and Humanities Department, LC2-3035-FOL

© BnF, Philosophy, History and Humanities Department, LC2-3035-FOL

Paul Nadar invested personally in the invention and production of new equipment. […] On November 13, 1903, he founded the Telegraphoscope Society to promote an invention of brothers Édouard and Marcel Belin that used electricity to transmit real optical images almost instanteously – an ancestor of television. The funds the society raised, from Paul’s father, among others, contributed to the development of the Belinograph, or wire-photo machine, a 1907 invention that allowed photographs to be sent remotely over telegraph and telephone wires, the origin of the photocopier.