II. The Art of the Portrait

There are not just one, but several Nadars. Along with Félix, his brother Adrien and son Paul also abandoned their last name and adopted the pseudonym that Félix had come up with. And yet, there is just one Nadar, more precisely a brand, a collective singular that refers not only to a family, but also to a firm that employed a great many collaborators. In the 19th century, Nadar was a brand with a powerful cultural aura.

Sarah Bernhardt, draped in white, Félix Nadar, around 1864

© BnF, Prints and Photographs Department, EO-15 (1)-PET FOL

Emmanuel Frémiet, Adrien Tournachon, around 1854-1855

© New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gilman Collection, Purchase, Alfred Stieglitz Society Gifts, 2005 (2005.100.45)

Going to Nadar’s studio and leaving with photographs signed, until the late 1870s, with the slender but striking red N, was a way of making a statement. Differentiation and distinction: in the 19th century, subtle social differences defined the world of photography. The competition between photographic studios, whose number mushroomed in the 1860s, led to a dual phenomenon. On the one hand, it resulted in specialization: none of the studios were generalists, each of them established their mastery in specific domains. On the other hand, the large portrait studios had different target audiences, making them socially identifiable. Tell me who took your portrait and how it was taken, and I’ll tell you who you are in society’s eyes. For example, during the Second Empire (1852-1870), Disdéri had a conservative clientele. His collections of calling cards and portraits focused essentially on representatives of French and foreign powers, as well as on well-known actresses and female dancers. Aside from the artistic set, Nadar’s studio, however, was essentially patronized by the liberal bourgeoisie. Red was not only the predominant color in the studio on Boulevard des Capucines, it was also the color associated with his anti-Royalist leanings, which contributed to publicizing it. According to Ernest Lacan, Nadar celebrated an “orgy of red” in his studio. Taken as a whole – the color, the name and the decor – was more than enough. The photographer’s presence was felt without his actually having to be there: customers were satisfied with the magical aura of his name. […]

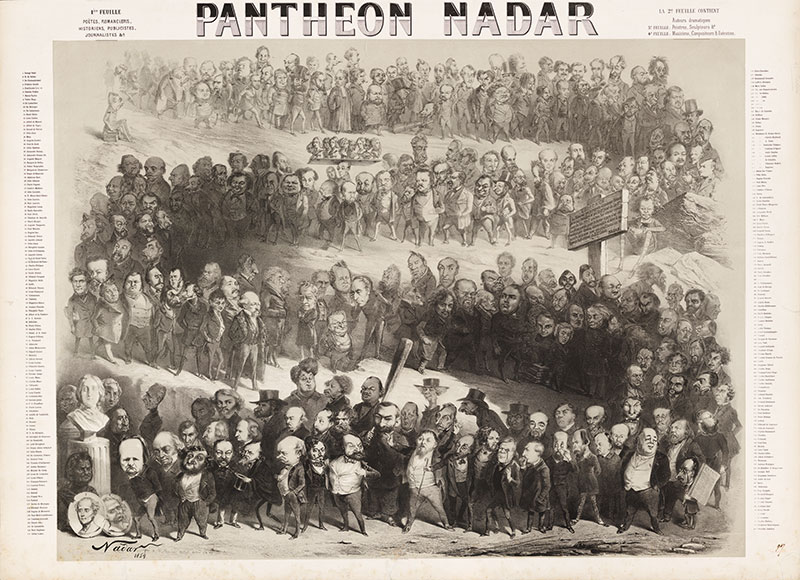

Nadar’s Pantheon

“To the gentleman who I most assuredly regret in advance not knowing, and who, on the 2nd day of the 3rd moon of the year 3067 will be dashing from one auction house to another like a lost dog, in order to purchase at an astronomical price this now exceedingly rare copy, which he simply must have for his major study of the great historical figures of the 19th century.”

Nadar’s Pantheon is the title of an ambitious series of four lithographs dreamt up by Nadar in 1852. They were intended to portray, in 1,200 caricature-portraits, first men of letters and journalists, then playwrights, then visual artists, and finally musicians, composers and performers. Each portrait was to be accompanied by a light-hearted biography.

Nadar’s career as a caricaturist began around 1846-1847. He contributed to some of the many small, illustrated newspapers that abounded under the July Monarchy: Corsaire-Satan, La Silhouette and more. Léo Lespè, a.k.a. Timothée Trimm, the editor-in-chief of the Journal du dimanche, commissioned him to create “one hundred portraits of writers, and a biographical note to accompany each portrait.” Published in August, 1847, this Gallery of Writers inaugurated Nadar’s reigning passion: portraying his contemporaries through drawing, photography, and writing.

Nadar’s career as a caricaturist began around 1846-1847. He contributed to some of the many small, illustrated newspapers that abounded under the July Monarchy: Corsaire-Satan, La Silhouette and more. Léo Lespè, a.k.a. Timothée Trimm, the editor-in-chief of the Journal du dimanche, commissioned him to create “one hundred portraits of writers, and a biographical note to accompany each portrait.” Published in August, 1847, this Gallery of Writers inaugurated Nadar’s reigning passion: portraying his contemporaries through drawing, photography, and writing.

1853 Tintamarre Almanach by Mathieu Lanceblague (Matthew Jokethrower), Félix Nadar, 1852

The illustrations are signed "Nadar" on the stone

© BnF, Prints and Photographs Department, TF-1133 (1)-FOL

© BnF, Prints and Photographs Department, TF-1133 (1)-FOL

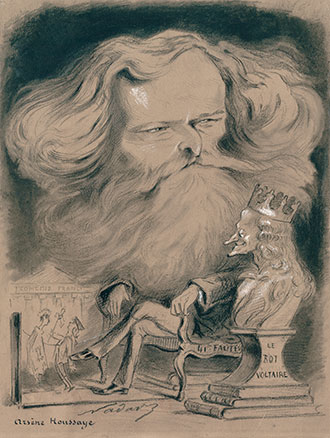

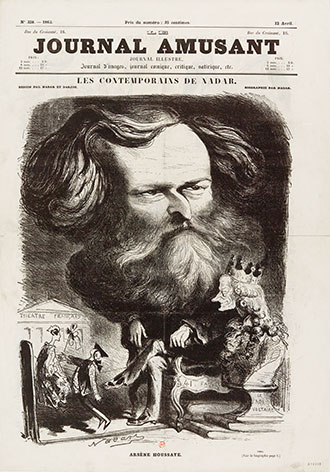

Arsène Houssaye sitting next to a bust labelled 'King Voltaire', 12 April 1862, Félix Nadar

Drawing not included in Nadar’s Pantheon: caricature from the "Nadar’s Contemporaries" series published in issue 328 of Le Journal amusant

© BnF, Prints and Photographs Department, STORAGE NA-88-ÉCU BOX

© BnF, Prints and Photographs Department, STORAGE NA-88-ÉCU BOX

It was his signature skill, which he perfected over the following years: he drew first for the Revue comique à l’usage des gens sérieux (The Comical Journal for Serious People) – signing his drawings Nadard or with a slightly forward-leaning capital N – then for Charles Philipon’s Journal pour rire (The Humorous Newspaper) and the Le Tintamarre. The period’s political instability was conducive to rebellion, caricature, and parodies that pulled the wool over the censor’s eyes. Nadar’s Jury, which made fun of the academic artwork in the Salon, debuted in 1852: the plates were published in L’Éclair, Le Tintamarre, Rabelais and the Journal amusant.

So it was an established illustrator, knighted by Philipon, the king of the satirical press, who came up with the Pantheon project, an avatar of previous publications by his mentor, particularly the Charivari Pantheon (1841) and the Great Path of Posterity (1842) by Benjamin Roubaud (1811-1847).

The year that he worked on the Pantheon was a hectic one for Nadar. He didn’t drop any of his other collaborations, instead he hired a small group of illustrators, including his younger brother, to draw the hundreds of images needed for those large group portraits. He wrote to his models asking them to come in to sit and requesting a biography from each. The year 1853 was taken up with composing the portraits, and above all, finding the financing, which barely trickled in, despite the unanimous support of his journalist friends. Polydore Millaud would save the day by purchasing 400 portraits from the Pantheon for 8,000 francs. The biographies weren’t ready yet, and by 1854, only the writers-and-journalists plate had been completed, by resorting to photography for some models, thanks to Adrien. After knocking themselves out for over a year, that first and only plate was finally published in February, 1854. A critical success but a financial failure, the project’s most significant outcome was that it made Nadar famous.

In 1858, a Pantheon with a cast of 270 (as opposed to the original 249) was published as a bonus with Le Figaro. Nadar, who by then was caught up with photography and a thousand other projects, gave up on the other three plates. He continued to mine the Pantheon vein for a long time, however, in a range of publications and sales, and to decorate his successive studios. In 1907-1908, for instance, a set of almost 600 drawings from the Pantheon, or in a similar spirit, were sold to the National Library. For the most part, they were premium charcoal versions with white gouache highlights, signed by Nadar.

So it was an established illustrator, knighted by Philipon, the king of the satirical press, who came up with the Pantheon project, an avatar of previous publications by his mentor, particularly the Charivari Pantheon (1841) and the Great Path of Posterity (1842) by Benjamin Roubaud (1811-1847).

The year that he worked on the Pantheon was a hectic one for Nadar. He didn’t drop any of his other collaborations, instead he hired a small group of illustrators, including his younger brother, to draw the hundreds of images needed for those large group portraits. He wrote to his models asking them to come in to sit and requesting a biography from each. The year 1853 was taken up with composing the portraits, and above all, finding the financing, which barely trickled in, despite the unanimous support of his journalist friends. Polydore Millaud would save the day by purchasing 400 portraits from the Pantheon for 8,000 francs. The biographies weren’t ready yet, and by 1854, only the writers-and-journalists plate had been completed, by resorting to photography for some models, thanks to Adrien. After knocking themselves out for over a year, that first and only plate was finally published in February, 1854. A critical success but a financial failure, the project’s most significant outcome was that it made Nadar famous.

In 1858, a Pantheon with a cast of 270 (as opposed to the original 249) was published as a bonus with Le Figaro. Nadar, who by then was caught up with photography and a thousand other projects, gave up on the other three plates. He continued to mine the Pantheon vein for a long time, however, in a range of publications and sales, and to decorate his successive studios. In 1907-1908, for instance, a set of almost 600 drawings from the Pantheon, or in a similar spirit, were sold to the National Library. For the most part, they were premium charcoal versions with white gouache highlights, signed by Nadar.

When, following in his younger brother’s footsteps, Nadar took up photography, he was enjoying a peak of renown thanks to the Pantheon, as well as nearly 20 years in Parisian newsrooms. He was famous and sociable, and he personified the enviable Parisian spirit to a T. When he got started, in 1854, everyone with good taste wanted to have their portrait taken, but the big commercial photographers on the boulevards didn’t suit them. Nadar provided the perfect combination of bohemian spirit and commercial product. In his studio, it finally became possible – without making concessions to vulgarity – to obtain a photographic portrait that was at once lifelike, flattering and artistic. Even Charles Baudelaire, that implacable detractor of absurd modern tastes, gave it a try. Félix decide to turn the apartment at 113 Rue Saint Lazare into a commercial photography studio. Although he did have some traditional patrons, the lion’s share of the clientele was made up of his bohemian friends.

“There is no such thing as an artistic photographer. Like everywhere else, in photography there are people who know how to see, and others who don’t even know how to look… Like in all trades, there are merchants and men with a conscience.”

Bohemian Life and Small Newspapers

Nadar’s contemporaries often expressed astonishment over his many lives and skills, among which one mustn’t forget his early penchant for literature. The Tournachons had been printer-booksellers in Lyon for generations, and young Félix, a fan of Alexandre Dumas, Victor Hugo and Honoré de Balzac, dreamt of becoming a writer. His schoolboy friendships with Charles Asselineau and Théodore de Banville, which date back to their early teens, then the adventure of the journal Le Livre d’or, gave him access to both high and low Parisian literary society by the time he was just 19 years old. He met Dumas père, Balzac, Théophile Gautier, Gérard de Nerval, and later, Henry Murger’s circle, the “Society of Water Drinkers,” whose adventures are described in Scenes from Bohemian Life. As early as 1842, when he had only written a few serialized stories, he joined the Société des gens de lettres, the writer’s organization founded by Balzac, Dumas, Hugo and George Sand. That was where, in 1853, he first met Charles Baudelaire. For over a decade, from age 19 to age 30, he frequented various bohemian circles, sharing their poverty, exaltation, adventures and freelance work for small newspapers, as well as the legendary dinners at the restaurant known as Dinocheau and the soirées at Café Momus. That was the period when he wrote and published novels and short stories, particularly La Robe de Déjanire (Deianire’s Dress, 1844), another scene from bohemian life, another group of friends in other garret rooms. The collected short stories published as Quand j’étais étudiant (When I Was a Student) and published in 1856 had all first appeared in small newspapers, such as Le Commerce or Le Voleur (The Thief).

Nadar, a faithful friend, stayed close to his companions from that time. He tended to Murger when the latter was on his deathbed. The year after his friend passed away, he, Léon Noël and Adrien Lelioux published a Histoire de Murger pour servir à l’histoire de la vraie bohème (A Story of Murger to Serve the History of True Bohemia). At that time, Nadar had just opened his studio on Boulevard des Capucines and was light-years away from his impoverished youth. During Baudelaire’s last days, in August, 1867, Nadar was equally loyal and present, and upon the poet’s death, he pleaded with Hippolyte de Villemessant, the head of Le Figaro, to publish an article that would be worthy of him “[…] about this gallant and talented man, all sorts of nonsense that will cruelly pain those who loved and respected him will be said. If you want the truth about him in your newspaper, I hereby offer to speak it.” The article, as sparingly titled as a tombstone, “Charles-Pierre Baudelaire,” ran on September 10, 1867. It displays tremendous sensitivity: “[…] I herein offer my account to one about whom much has been said but little is truly known,” Nadar says as a preamble. His posthumous book, Charles Baudelaire intime : le poète vierge (An Intimate Portrait of Charles Baudelaire: The Virgin Poet), written with the help of Jacques Crépet, wasn’t published until 1911. Along with the tribute to Murger, it is undoubtedly one of the best first-person accounts to be found of the bohemian years. Nadar’s profound attachment to those heroic youthful years can also be found in his best photographic portraits. They’re all there: the poets and novelists, the chroniclers of his youth, and it is undoubtedly they who, along with the photographer’s own talent, contributed the most to his work’s remaining in the public eye for so long. As late as the 1930’s, Paul and Marthe Nadar were still getting requests for those bohemians’ portraits.

Nadar, a faithful friend, stayed close to his companions from that time. He tended to Murger when the latter was on his deathbed. The year after his friend passed away, he, Léon Noël and Adrien Lelioux published a Histoire de Murger pour servir à l’histoire de la vraie bohème (A Story of Murger to Serve the History of True Bohemia). At that time, Nadar had just opened his studio on Boulevard des Capucines and was light-years away from his impoverished youth. During Baudelaire’s last days, in August, 1867, Nadar was equally loyal and present, and upon the poet’s death, he pleaded with Hippolyte de Villemessant, the head of Le Figaro, to publish an article that would be worthy of him “[…] about this gallant and talented man, all sorts of nonsense that will cruelly pain those who loved and respected him will be said. If you want the truth about him in your newspaper, I hereby offer to speak it.” The article, as sparingly titled as a tombstone, “Charles-Pierre Baudelaire,” ran on September 10, 1867. It displays tremendous sensitivity: “[…] I herein offer my account to one about whom much has been said but little is truly known,” Nadar says as a preamble. His posthumous book, Charles Baudelaire intime : le poète vierge (An Intimate Portrait of Charles Baudelaire: The Virgin Poet), written with the help of Jacques Crépet, wasn’t published until 1911. Along with the tribute to Murger, it is undoubtedly one of the best first-person accounts to be found of the bohemian years. Nadar’s profound attachment to those heroic youthful years can also be found in his best photographic portraits. They’re all there: the poets and novelists, the chroniclers of his youth, and it is undoubtedly they who, along with the photographer’s own talent, contributed the most to his work’s remaining in the public eye for so long. As late as the 1930’s, Paul and Marthe Nadar were still getting requests for those bohemians’ portraits.

The Nadars’ various studios bore witness to the business’s ups and downs over the course of a century. Of a modest size at first, their second, cathedral-like studios symbolized the Golden Age of the Nadar enterprise.

The Studios

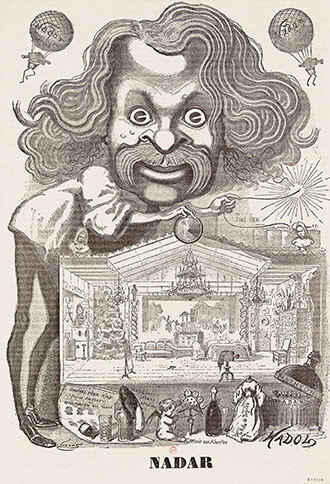

Caricature of Nadar as a marionnettist, pulling the strings at this studio, 17 March 1861, Paul Hadol (1835-1875)

Caricature that appeared in Le Gaulois: Petite gazette critique, satirique et anecdotique

© BnF, Prints and Photographs Department, EO-15 (3)-FOL

© BnF, Prints and Photographs Department, EO-15 (3)-FOL

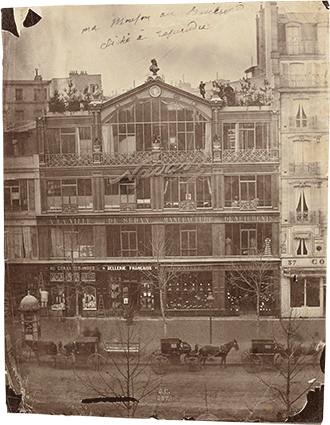

Adrien invested in a mansion on the Champs Élysées, which has been described as a “somber monument” made of smooth, angular dimension stone and adorned with columns and an attic level. Félix choose the building that had formerly been occupied by the Bisson brothers and Gustave Le Gray, at 35 Boulevard des Capucines, in a neighborhood that was gentrifying quickly, thanks to the the construction of the Grand Hôtel and the new Opera House. Its façade and interior decoration could compete with the ostentatiousness of the era’s biggest studios. Such impressive infrastructures, and their staff, considerably increased their business’s expenses. After the studio on Boulevard des Capucines declared bankruptcy, Félix and Ernestine transferred their activity to more reasonable premises on Rue d’Anjou.

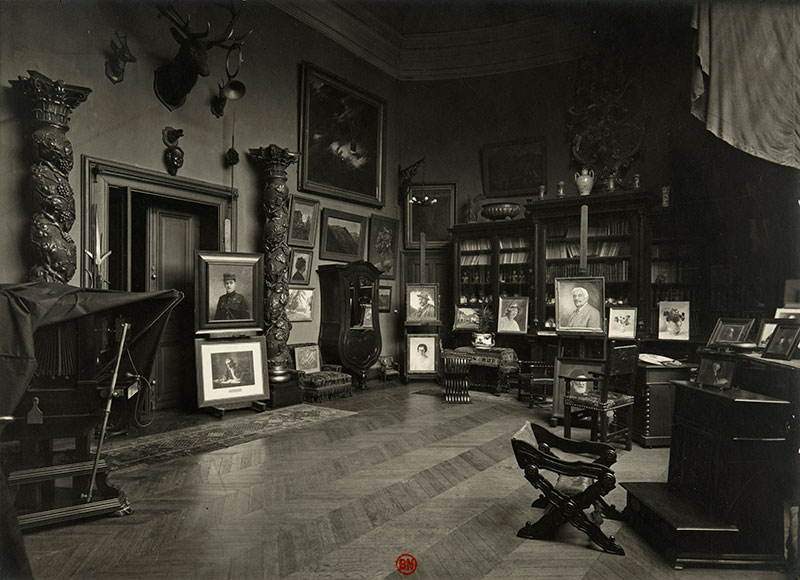

Before the advent of artificial light and more sensitive processes, natural light was indispensable for taking and developing photographs. Therefore, the first Nadar studios included outdoor areas: a rooftop terrace for Adrien and a ground floor with a garden and a glass-roofed atrium for Félix. On the upper floors, huge windows allowed him to take advantage of as much light as possible. The photographers could create a range of variations and effects thanks to blinds that filtered the light, and by using reflectors and screens. The interior arrangements were inspired by artists’ studios, and in 1924, Paul Nadar actually took over Léon Bonnat’s mansion on Rue de Bassano.

Clients’ path from the entrance to the portrait studio itself was designed as a sort of initiatory journey, offering a preview of the photographers’ personalities and their approach to portraiture. The studio was not unlike a blatantly luxurious cabinet of curiosities, in which an accumulation of objects and furnishings from all eras and places was piled up, in a sort of parody of a painter studio.

The photographers flaunted their medium’s modernism by incorporating all the latest innovations into their premises. The façade of the building on Boulevard des Capucines – adorned by the sculptor Émile Blavier’s Three Graces and illuminated by a gigantic, gas-lit version of the Nadar signature, designed by Antoine Lumière – was emblematic of the pairing of the fine arts and technical progress that was so characteristic of Second Empire style. The building was also equipped with one of the world’s first elevators. An up-to-date central-heating system with a huge room-heater decorated with glazed tiles, bronzes and enamels circulated warm air in winter. In summer, a thin stream of water running from the upper windows to an indoor, rock-lined cascade kept the premises cool.

The photographers flaunted their medium’s modernism by incorporating all the latest innovations into their premises. The façade of the building on Boulevard des Capucines – adorned by the sculptor Émile Blavier’s Three Graces and illuminated by a gigantic, gas-lit version of the Nadar signature, designed by Antoine Lumière – was emblematic of the pairing of the fine arts and technical progress that was so characteristic of Second Empire style. The building was also equipped with one of the world’s first elevators. An up-to-date central-heating system with a huge room-heater decorated with glazed tiles, bronzes and enamels circulated warm air in winter. In summer, a thin stream of water running from the upper windows to an indoor, rock-lined cascade kept the premises cool.

Interior of the studio at 35 Boulevard des Capucines, Félix Nadar, around 1861

© BnF, Prints and Photographs Department, EO-15 (1)-FOL

View of the interior of the studio at 35 Boulevard des Capucines, with Nadar's Pantheon, Félix Nadar, around 1861

© BnF, Prints and Photographs Department, EO-15 (1)-FOL

“Photographic theory can be learned in an hour; the basic notions of photographic practice, in a day... I shall tell you what can’t be learned: a feel for light, an artistic appreciation of the effects produced by varied, combined sources of light… What can be learned even less is a moral understanding of your subject, the rapid tact that puts you in communication with the model, and allows you to provide, not... an indifferent physical reproduction that is within the grasp of the lowliest servant in the laboratory, but the most familiar, most favorable and most intimately lifelike resemblance. It’s the psychological side of photography; the word does not seem to be an overstatement to me.”

Portraiture

Adrien Tournachon

Begun in 1854, Adrien Tournachon’s career as a photographer had come to en end by 1861. That brevity was not uncommon during those years when many people dove enthusiastically into the new art form, but it does contrast sharply with the longevity of Félix and Paul’s undertaking. What’s more, he tried out a range of different specialties, never devoting his time entirely to portraiture. Trained as a painter – and at heart he remained a painter, even as a photographer – he was introduced to photography by Gustave Le Gray, another painter-turned-photographer, who guided him in understanding photography’s artistic possibilities. […]

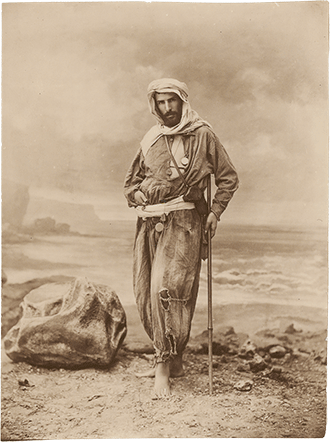

His best portraits are well lit, taken in relative close-up in harsh direct sunlight. The result is high contrasts, subjects casting strong shadows, and crisp distinctions between black and white. He has a weakness for low-angle shots. His clientele, swelled at first by his older brother’s extensive network of friends during their early partnership, then by his own musician partners, Jules Lefort and Louis James Alfred Lefébure-Wely, who got him the royal title “the Empress’s photographer” – thereby provoking his anti-Royalist brother’s ire – included a great many celebrities from artistic and bohemian circles: Alphonse de Lamartine, Alfred Vernet, Emmanuel Frémiet, Jean-Pierre Dantan, Jean-Gaspard Deburau, Gérard de Nerval, the Goncourt brothers, Gioachino Rossini, Musette and Théodore de Banville. He did some lovely picturesque costumed studies – shepherds, equestrians and pifferari – alongside studies of animals taken at agricultural shows that attracted competitors from a number of different countries. In terms of portraiture, Adrien Tournachon’s body of work, one of the most personal ones from an era when fawning mediocrity flourished, also stands out for its unusual dimensions (generally 30 × 20 cm) and his signature use of very glossy paper, which provided both shine and transparency. Yet, suffering from both dispersal and confusion with the work of his brother, its true worth has yet to be fully appraised.

Félix Nadar

The tribute the photographer and journalist Henri Tournier paid to Félix Nadar in 1859, when the latter was at the peak of his art, summarizes the qualities that made him famous then, and have kept him famous to this day:

“Speaking of portraiture means speaking of Mr. Nadar and of his contemporary portrait gallery, which he signs with a powerful N, the same one that signals the famous studio at number 113, Rue Saint Lazare. That N is like the mark of a lion. […] Mr. Nadar is a colorist, the word is rarely used, yet it is accurate. For anyone who knows Mr. Nadar, there’s something about his style; his face, which reminds one, in an ugly way, of Rembrandt’s; his flair, his panache and his ardor, something of the audacity that reveals an ingrained horror for outlines and dry tones.

Everyone who is anyone in literature, the arts, finance or the bar has come to pose for his lens and enrich his collection of contemporary figures. […].

The advantage of Mr. Nadar’s portraits does not consist only in the cleverness of the pose, which is as artistic as can be. There is also a skillful and well-thought-out arrangement of the light, which attenuates or increases visibility depending on the face’s character and the operator’s instinct. In addition, looking at how the photographs are printed, we find a subtle search for harmony and slightly faded tones that soften sharp edges with their twilight effect.

There you have them, the celebrities of the day. The Olympian Théophile Gautier in full color, his forehead girded in bright madras […]. The light captured Jules Janin’s fleetingly delicate and sensual smile, Alexandre Dumas’s refined bonhomie, François Guizot’s disdain, and Eugène Pelletan’s daydreaming. Caught by a ray of sun, and immortalized by it, they have all left their originality and even a bit of their soul on the plate.

Such delicacy in the women’s heads! One in particular is a masterpiece of grace and know-how: a supple neck crowned with opulent tresses, nobly attached to the shoulders, bestow upon this face a poetry that is rarely found outside an ideally composed portrait.

All of the heads seem natural; none have succumbed to the boredom of terraces and head-rests. Nadar has his models pose in a garden where there is more to breathe than just the emanations of the ether. Besides, only clever and witty people pose for him. It wouldn’t be like them to lose their intelligent look in front of a lens; it wouldn’t be like Nadar not to manage to preserve it for them.”

“Speaking of portraiture means speaking of Mr. Nadar and of his contemporary portrait gallery, which he signs with a powerful N, the same one that signals the famous studio at number 113, Rue Saint Lazare. That N is like the mark of a lion. […] Mr. Nadar is a colorist, the word is rarely used, yet it is accurate. For anyone who knows Mr. Nadar, there’s something about his style; his face, which reminds one, in an ugly way, of Rembrandt’s; his flair, his panache and his ardor, something of the audacity that reveals an ingrained horror for outlines and dry tones.

Everyone who is anyone in literature, the arts, finance or the bar has come to pose for his lens and enrich his collection of contemporary figures. […].

The advantage of Mr. Nadar’s portraits does not consist only in the cleverness of the pose, which is as artistic as can be. There is also a skillful and well-thought-out arrangement of the light, which attenuates or increases visibility depending on the face’s character and the operator’s instinct. In addition, looking at how the photographs are printed, we find a subtle search for harmony and slightly faded tones that soften sharp edges with their twilight effect.

There you have them, the celebrities of the day. The Olympian Théophile Gautier in full color, his forehead girded in bright madras […]. The light captured Jules Janin’s fleetingly delicate and sensual smile, Alexandre Dumas’s refined bonhomie, François Guizot’s disdain, and Eugène Pelletan’s daydreaming. Caught by a ray of sun, and immortalized by it, they have all left their originality and even a bit of their soul on the plate.

Such delicacy in the women’s heads! One in particular is a masterpiece of grace and know-how: a supple neck crowned with opulent tresses, nobly attached to the shoulders, bestow upon this face a poetry that is rarely found outside an ideally composed portrait.

All of the heads seem natural; none have succumbed to the boredom of terraces and head-rests. Nadar has his models pose in a garden where there is more to breathe than just the emanations of the ether. Besides, only clever and witty people pose for him. It wouldn’t be like them to lose their intelligent look in front of a lens; it wouldn’t be like Nadar not to manage to preserve it for them.”

Paul Nadar

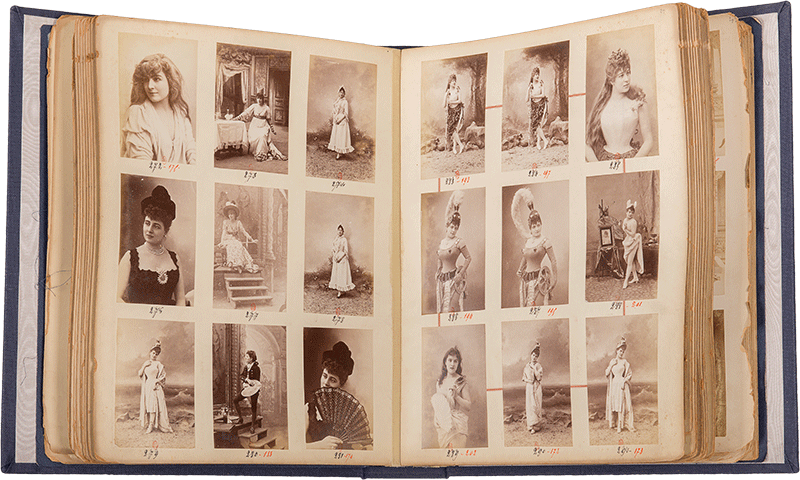

Under Paul Nadar’s leadership, the studio proposed an approach to portraiture that was radically opposed to the esthetic of his father’s and uncle’s earliest portraits. Although in the early 1880s, Nadar portraits stood out for their plain backgrounds, Paul granted tremendous importance to the task of composing the scene, which constituted the photographer’s “personal and artistic” work.

His sitters always posed in front of a painted trompe-l’oeil backdrop, as was the fashion of the time. Clients could use a system of rotating panoramas to choose a scene from among those that unspooled before their eyes. Paul Nadar stood out for his attention to detail and his taste for staging. Some of his portraits, like the one of the explorer Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza in the desert, can be compared to the photographs he took of the performing arts. He offered a wide range of scenes and settings recreated in the studio, as well as photomontages presenting the portraits in artistic frames. Paul also paid great attention to the layout, arranging his sitters in such a way as to create a highly refined whole, particularly for his “tableaux vivants,” which were very fashionable in the early 20th century. His skill with lighting also contributed to the success of his portraits, which, while preserving subjects’ individuality, were also as flattering as could be.

Influenced by Pictorialism (1890-1914), Paul Nadar would develop the art of retouching: he worked directly on the negatives to blur lines, explored different print methods (platinum process, gum bichromate, carbon process) and various pigment processes in order to bring out his prints’ pictorial qualities; he even tried colorization. Using those techniques, he had no qualms about reworking the series of celebrity portraits shot by his father. In that particular case, the retouching work was so involved that it offered a veritable reinterpretation of the original negative.

The 1920s confirmed Paul’s attention to and capacity for adapting to photography’s esthetic evolutions. His unadorned portraits focused on faces with spontaneous expressions were closer than ever before to the original Nadar look. As he succinctly put it when he announced that his business was moving to Rue de Bassano in 1924, his portraiture was based, “above all, and independently of any issues of taste or elegance, upon aiming for a lifelike resemblance through the expression and the TRUTH.”

Influenced by Pictorialism (1890-1914), Paul Nadar would develop the art of retouching: he worked directly on the negatives to blur lines, explored different print methods (platinum process, gum bichromate, carbon process) and various pigment processes in order to bring out his prints’ pictorial qualities; he even tried colorization. Using those techniques, he had no qualms about reworking the series of celebrity portraits shot by his father. In that particular case, the retouching work was so involved that it offered a veritable reinterpretation of the original negative.

The 1920s confirmed Paul’s attention to and capacity for adapting to photography’s esthetic evolutions. His unadorned portraits focused on faces with spontaneous expressions were closer than ever before to the original Nadar look. As he succinctly put it when he announced that his business was moving to Rue de Bassano in 1924, his portraiture was based, “above all, and independently of any issues of taste or elegance, upon aiming for a lifelike resemblance through the expression and the TRUTH.”

Up until the 1880s, Félix Nadar’s portraits stood out for their plain backgrounds. Paul Nadar, on the other hand, would later grant tremendous importance to the task of composing the scene, which constituted the photographer’s “personal and artistic” work. A devoted light-opera-goer, Paul was most Parisian theaters’ house photographer. From 1888 on, portraits of actors and opera singers became one of the studio’s main commercial ventures. As for Adrien Tournachon, he also snapped the celebrities of his era, becoming a professional photographer without giving up his work as a painter.

The Performing Arts

In 1855, the performing arts earned Adrien Tournachon the greatest honor of his photographic career, when he was awarded the gold medal at the World’s Fair for his Têtes d’expression de Pierrot (Pierrot the Clown’s Expressive Faces). While Félix probably had the idea for the project, Adrien signed the series of prints whose play of light immortalized a youthful Jean-Gaspard Deburau’s expressive body language and precise miming. His excellent eye for photography, which was probably honed by his training as a painter, was confirmed when he photographed the performances of the Empress’s Circus. Adrien Tournachon’s portraits of Gioachino Rossini and Giacomo Meyerbeer vouch for his ties to the world of music, thanks to the tenor Lefort and organist Louis James Alfred Lefébure-Wely, with whom he formed a partnership in 1855.

Félix Nadar was able to take advantage of an established network right from the start of his photographic career: “Everyone was always welcome at the Nadars. In their home, Alexandre Dumas père rubbed shoulders with Jacques Offenbach, Victorien Sardou mixed with Gustave Doré, and the distinguished actors of the Comédie Française troupe mingled with Henri Rochefort.” He made a portrait of his friends the Darciers, which was later reproduced as a poster for the Bouffes-Parisiens theatre – and of Offenbach, who bankrolled the “Artistic Photography Society,” which he founded in January, 1856. In his commissioned portraits of actors and singers, he aimed to expose their own personalities rather than to flaunt their skill as performers.

That branch of the business was developed at the studio on Rue d’Anjou, and in the late 1880s, under Paul Nadar’s leadership, it became a Nadar specialty.

As a devoted opera buff, with a subscription to the Opéra-Comique and close ties to the soprano Marie Degrandi, Paul produced a major visual archive of the shows performed at all the main Parisian opera houses and musical theatres from 1880 to 1920, with a particular focus on the Symbolist movement. His work stands out for the care he devoted to staging his photographs, recreating the performances’ main scenes in his studio and offering a wide range of trompe-l’oeil painted backdrops, sometimes even including an exact replica of the original scenery. His attention to detail went so far as to choose an angle that provided a similar point of view as to what one would see at the theatre. With the help of artificial light (electricity and magnesium), he attempted photographing performers during rehearsals, but the results were disappointing compared to what he could achieve in the studio. Paul Nadar was also actively involved with the Paris Opera from the 1890s on. Succeeding Wilhelm Benque as the institution’s official photographer, he held the post from 1898 until World War I. Unlike the scantily clad shots that were the norm of his day, Paul Nadar’s many individual portraits of actresses and female singers and dancers stand out for their elegance. The performing arts composed Paul Nadar’s main contribution to the “Gallery of Contemporaries” that his father had begun.

Félix Nadar was able to take advantage of an established network right from the start of his photographic career: “Everyone was always welcome at the Nadars. In their home, Alexandre Dumas père rubbed shoulders with Jacques Offenbach, Victorien Sardou mixed with Gustave Doré, and the distinguished actors of the Comédie Française troupe mingled with Henri Rochefort.” He made a portrait of his friends the Darciers, which was later reproduced as a poster for the Bouffes-Parisiens theatre – and of Offenbach, who bankrolled the “Artistic Photography Society,” which he founded in January, 1856. In his commissioned portraits of actors and singers, he aimed to expose their own personalities rather than to flaunt their skill as performers.

That branch of the business was developed at the studio on Rue d’Anjou, and in the late 1880s, under Paul Nadar’s leadership, it became a Nadar specialty.

As a devoted opera buff, with a subscription to the Opéra-Comique and close ties to the soprano Marie Degrandi, Paul produced a major visual archive of the shows performed at all the main Parisian opera houses and musical theatres from 1880 to 1920, with a particular focus on the Symbolist movement. His work stands out for the care he devoted to staging his photographs, recreating the performances’ main scenes in his studio and offering a wide range of trompe-l’oeil painted backdrops, sometimes even including an exact replica of the original scenery. His attention to detail went so far as to choose an angle that provided a similar point of view as to what one would see at the theatre. With the help of artificial light (electricity and magnesium), he attempted photographing performers during rehearsals, but the results were disappointing compared to what he could achieve in the studio. Paul Nadar was also actively involved with the Paris Opera from the 1890s on. Succeeding Wilhelm Benque as the institution’s official photographer, he held the post from 1898 until World War I. Unlike the scantily clad shots that were the norm of his day, Paul Nadar’s many individual portraits of actresses and female singers and dancers stand out for their elegance. The performing arts composed Paul Nadar’s main contribution to the “Gallery of Contemporaries” that his father had begun.